In 2019, Princess Elizabeth Primary School (PEPS) established its

Applied Learning Programme (ALP) in Innovation and Entreprise. What

was the intention behind this?

It aims to develop design thinking capabilities in students

across all levels in our school to foster inclusivity through building

empathy and inventive thinking skills. As part of the programme,

students learn and apply design thinking to address societal issues,

including social integration of seniors and inter-generational cohesion.

What is an example of a project under this ALP?

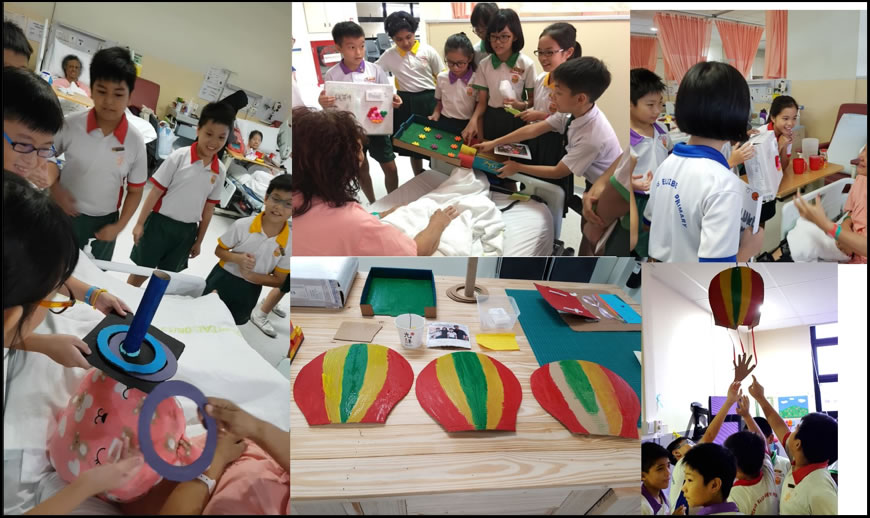

We involved a group of Primary 5 and 6 student leaders to work

with patients at St. Luke’s Hospital. This community hospital cares for

chronically ill patients as well as those that require rehabilitation

through physiotherapy. To understand the patients’ needs, the student

leaders interviewed them to in order to gain empathy, and

develop insights into the issues surrounding the user experience of

physiotherapy. Through a series of discussions and reflections, the

student leaders decided to focus on the problem of patients who were

unwilling to undergo physiotherapy due to a lack of motivation.

Student

leaders learning more about St. Luke's and understanding the

challenges the patients face.

Student

leaders learning more about St. Luke's and understanding the

challenges the patients face.

What solutions did the student leaders come up with?

In the Imagine (Ideate) stage, the student leaders generated as many

ideas and solutions as possible. After brainstorming, substituting,

combining and modifying some of the ideas, they decided to prototype

ways to gamify the physiotherapy

process to make the experience more engaging for the patients. These

were translated into interactive games and sensory boards made out of

recycled materials and whatever could be found in PEPS InnoSpace, a

maker space that is set up in our

school.

In the Prototyping and Making stage, the student leaders spent a few consecutive weeks to make the prototypes, obtained feedback from the staff in St. Luke’s and refined their solutions. The iterative process enabled them to develop a sensitivity to their designs to meet the needs of the patients.

The

prototyping and making stages being executed at PEPS’ InnoSpace

(Maker Space).

The

prototyping and making stages being executed at PEPS’ InnoSpace

(Maker Space).

How did the patients respond to the solutions?

The entire process took about a year and included two site visits. The

student leaders

interacted with the patients in St. Luke’s through playing the games

they created. It

was evident that the patients were more engaged as they were indirectly

undergoing

physiotherapy through the games. They also seemed to enjoy the energy

and

company of the student leaders tremendously. We could tell this from the

way some

patients did not want to stop interacting with the student leaders,

while others

encouraged them to go over and “play”.

The

prototyping and making stages being executed at PEPS’ InnoSpace

(Maker Space).

The

prototyping and making stages being executed at PEPS’ InnoSpace

(Maker Space).

Through this journey, the student leaders grew to understand how design thinking can enrich the experience of the people they wish to serve. This in turn supports our school’s mission of nurturing their capacity to embrace and celebrate diversity so that no one is left behind. Additionally, our school advocates servant leadership, where the qualities include listening, community building and empathy, all of which are synonymous with inclusive design thinking principles. These were honed during this ALP, allowing the students to further develop their leadership abilities.

The Premise: Designers from a multi-disciplinary background are highly valued for their ability to apply different methodologies to tackle a problem.

The Project: Ngee Ann Polytechnic’s School of Design & Environment integrated knowledge and skills from two different diplomas – Sustainable Urban Design and Engineering (SDE) and Product Design and Innovation (PDI) – to encourage their students to help Kampung Naga, a traditional Sundanese community in West Java in Indonesia, to co-design and co-create a kindergarten.

The students approached the projects with the participatory design

methodology framework, along with the Polytechnic’s signature service

learning pedagogy. This allowed them to empathise with, and understand

the needs of the community and

immerse themselves in their culture before using their design skills and

knowledge to create sustainable and meaningful solutions.

Also contributing to the project was etc.lab, an interdisciplinary centre that is part of the School that does research to empower communities through design.

When: March 2019

Lecturers: Raja Mohammad Fairuz Bin Mohamad Yusoff and

Jason Khiang Jian Hao

Furniture Industry Partners: Cellini, Djalin

Community Partners: Kampung Naga, HIPANA

The Participatory Design Process:

1. DISCOVER | Along with Kampung Naga’s village head and

leaders, and community partners HIPANA, the lecturers planned

participatory workshops for the students to learn and understand the

community’s needs, local materials and

crafting techniques. The SDE and PDI students then engaged with

villagers from Kampung Naga to understand the opportunities, immerse

themselves in the culture and co-designed solutions to meet their needs.

Applying their knowledge

of architecture and product design, they helped translate the needs of

the villagers into feasible ideas. All these enabled them to build

rapport with the local community, leading to a fruitful co-creating

experience.

The students

engaging with the villagers to understand their needs.

2. DEFINE | The students interpreted and framed inputs from the interviews and creative community engagements into different opportunities. Based on that, they identified common themes and used provocative “How might we?” questions to generate concepts to address the community’s needs. They iterated and co-created these with the community through multiple feedback sessions. Co-creating and co-designing with the community created and instilled a huge sense of ownership towards the design of the kindergarten.

Working

through a feedback session with the villagers.

3. DEVELOP | Since the designs had to be validated with the community before implementation, the students built prototypes and mock-ups of their ideas and developed their concepts based on the stakeholders’ feedback.

Constructing

the prototype of the furniture and model of the kindergarten.

4. DELIVER | In the final step, the students co-built and co-fabricated the kindergarten and the accompanying furniture with the community and industry partners. This facilitated rapport building and bonding with the community.

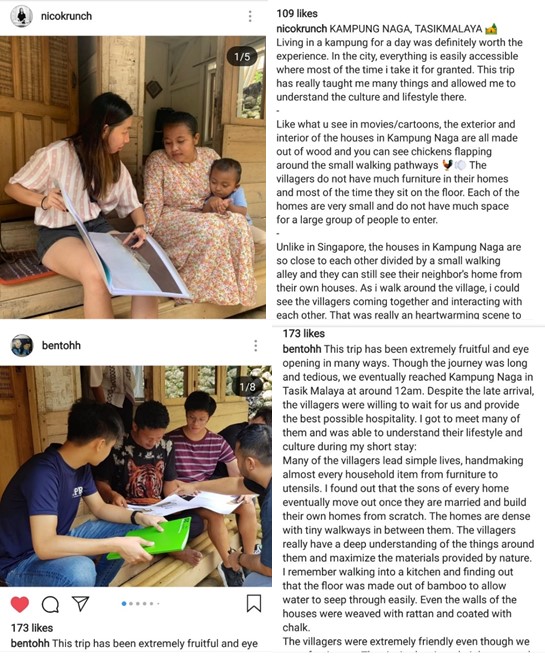

The Impact: | The students reflected on the project through elaborate, evocative posts on Instagram. After graduation, those involved returned on a graduation trip to Kampung Naga to render further assistance with the construction and refurbishment of the kindergarten.

Instagram

posts published by the students reflecting on the project.

etc.lab also curated exhibitions for the students to share their experience and insights from the participatory design experience with the design community in Singapore at events like the International Furniture Fair Singapore and BEX Asia. Through these, Ngee Ann Polytechnic has gained more industry collaborators and communities that are interested to apply and try this methodology. The exchange of views also provided feedback on how to further improve the School’s participatory design initiatives, which will be implemented in its future runs.

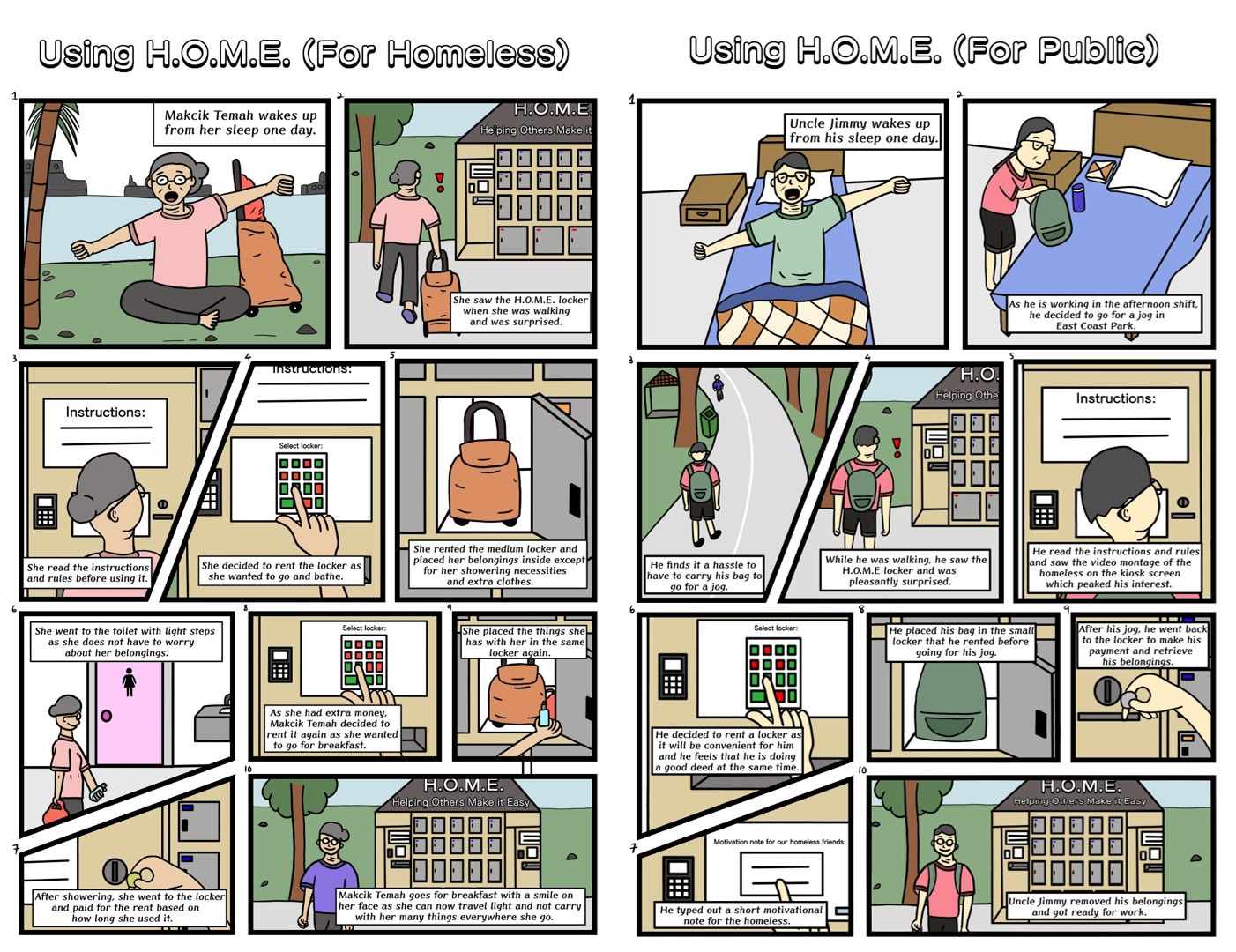

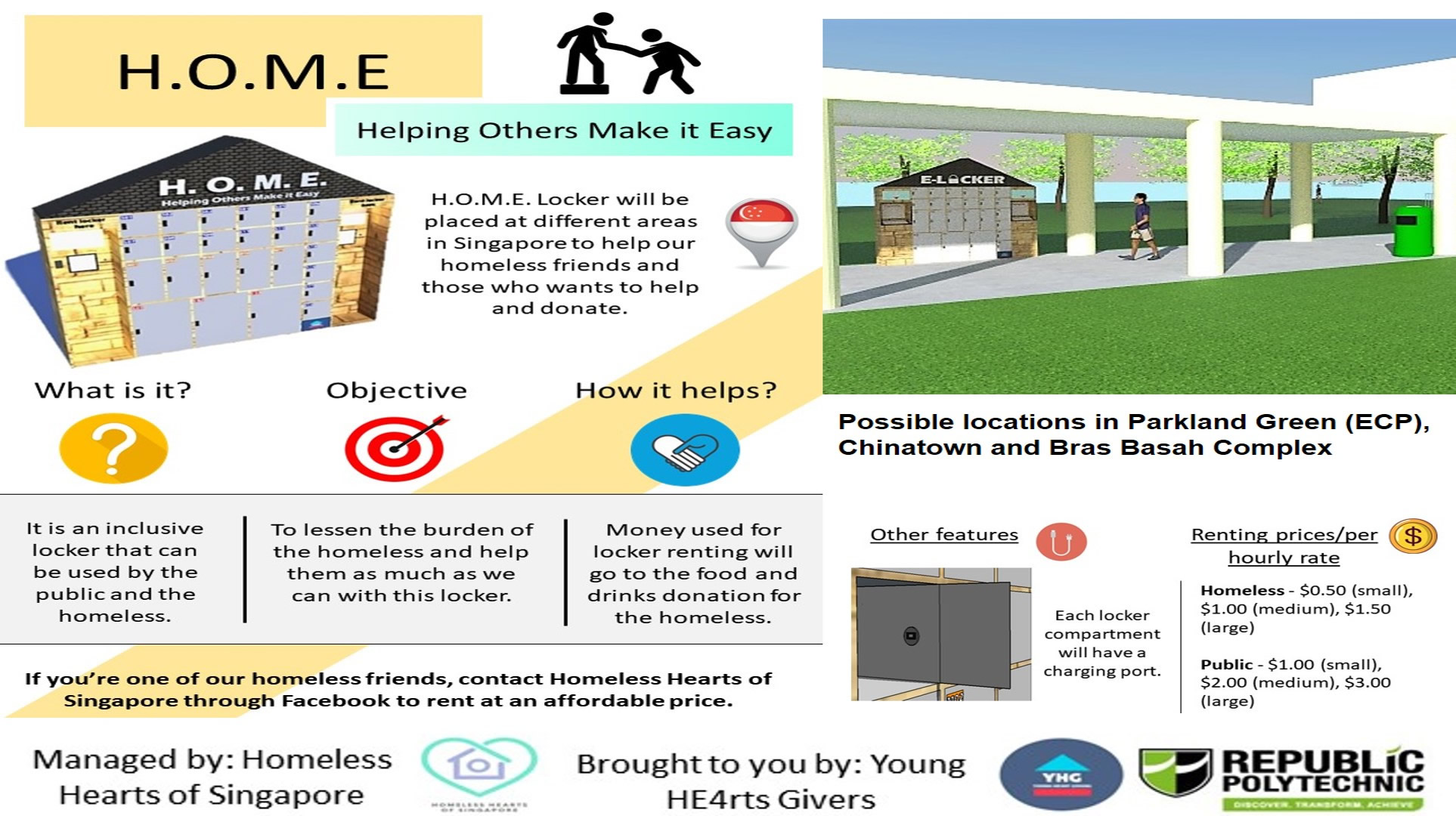

1,000 – this is the approximate number of homeless people in Singapore.

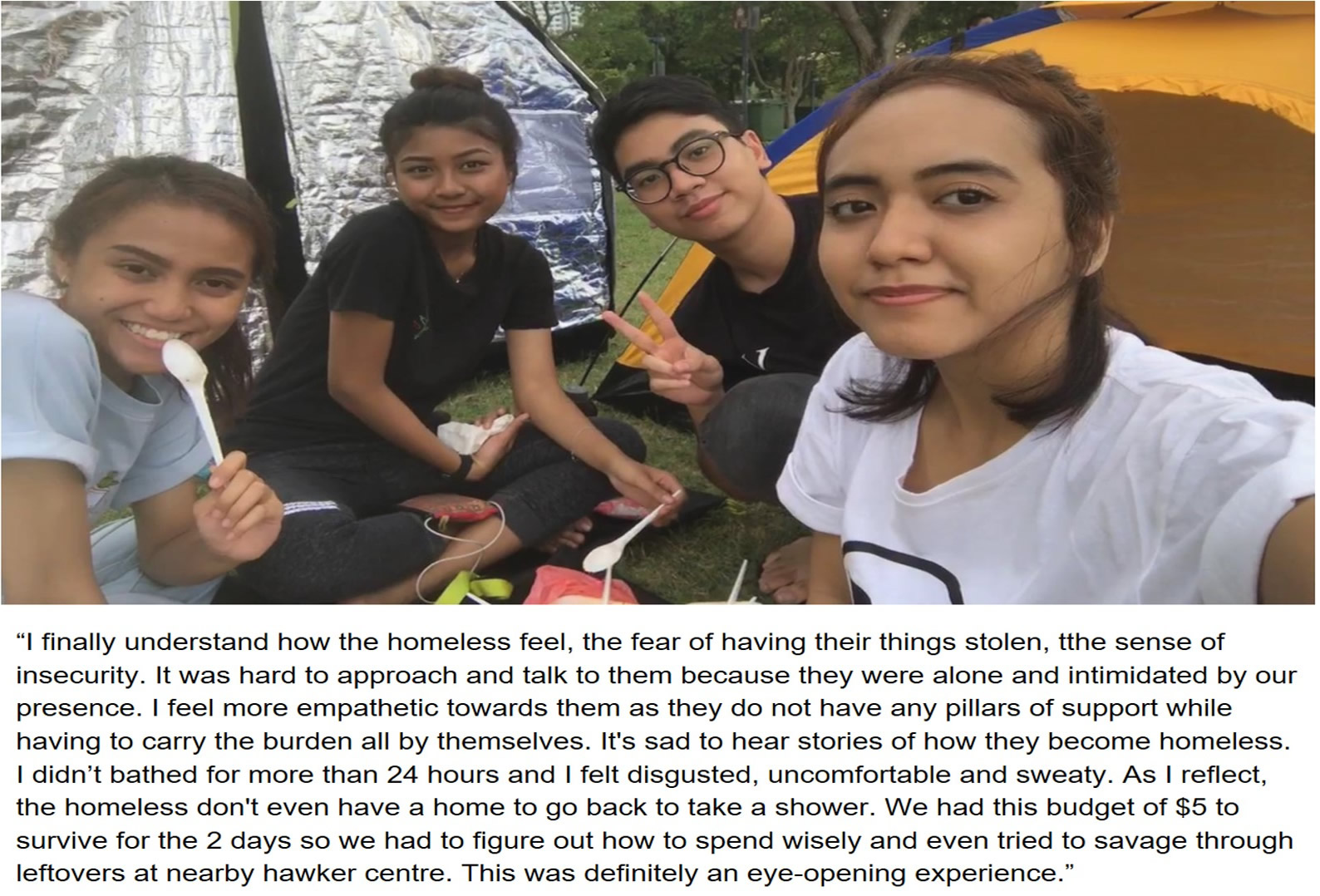

A group of four students from Republic Polytechnic’s Diploma in Design for User Experience was shocked to learn this, while volunteering at the Homeless Hearts of Singapore (HHOS).

Two of them, Nurlina Bte Mohamad and Nurul Ashiqin Bte Roslan, had chanced upon a homeless man on a school trip to Hong Kong.

Moved by the encounter, they teamed up with course mates Nadhirah Binte Hady and Muhammad Asyraf Bin Mohd Yazid when they returned to Singapore to volunteer at HHOS to explore how they could use design to improve the plight of the homeless.

Their findings went towards their final-year project, supervised by lecturer Mr Kong, in which they applied design thinking and problem-based learning to a cause they were passionate about.

“As part of design research, we encourage students to explore various methods to understand the user’s needs,” says Mr Kong.

“Through HHOS, the students distributed food and befriended the homeless hidden in pockets of the central business district.”

Along the way, they discovered the main reasons for homelessness in Singapore were family relationship problems.

They also learnt that the homeless have a fear of losing their belongings, since they do not have storage space to call their own.

As a result, these people are disconnected from society and there is a need to bridge the gap.

Around this time, the President*s Design Award team from DesignSingapore Council approached Mr Kong for an engagement activity as part of their outreach efforts. The proposal was for students to solicit ideas to improve the weatherHYDE tent, an all-seasons tent that won the Design of the Year accolade in the 2018 President*s Design Award. Through the DesignSingapore Council , the students were introduced to Prasoon Kumar, co-founder and CEO of Billion Bricks, which empowers everyone to be a homeowner.

“Inspired, the students initiated a two-day structured experience to stay in the tent at East Coast Park to test the product in the Singapore context.

“They also wanted to experience a day in the life of a homeless with limited cash, to find and interview the homeless there.”

Mr Kong says the students described it as “an eye-opening experience” and empathised with the homeless’ lack of insecurity and not being able to take regular showers. They also gave valuable feedback on how weatherHYDE tent may be modified for the Singapore climate and context, where the main issue is not shelter, but relationship problems and lack of social interaction.

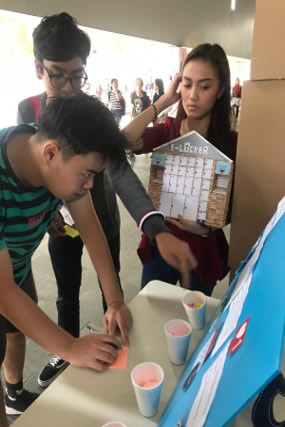

As a result of these research and experiences, the students decided to create a meaningful place with a locker system for rental to both the homeless and the public, which also acts as a place for social interaction and integration of the homeless back into society.

To this end, they conducted a poll in school to gather feedback on their idea.

A

participatory design poll at Republic Polytechnic.

A

participatory design poll at Republic Polytechnic.

The resultant business model they conceived involved charging the public to use the lockers at a higher rate, with the revenue going to HHOS to buy food and drinks for the homeless.

A video shown at the payment screen raises awareness of the homeless and allows the public to post encouraging messages which will be shown on the screen to the homeless when they use the lockers.

A poster showing

how H.O.M.E. works.

A poster showing

how H.O.M.E. works.

Mr Kong says the design has been well-received by HHOS and they plan to submit it to the Citi-YMCA Youth for Causes initiative to get a grant to implement it.

“This is a good example of how we promote self-directed learning for students to integrate their design skills with overseas exposure, industry expertise and social responsibility to produce innovative design solutions,” he adds.

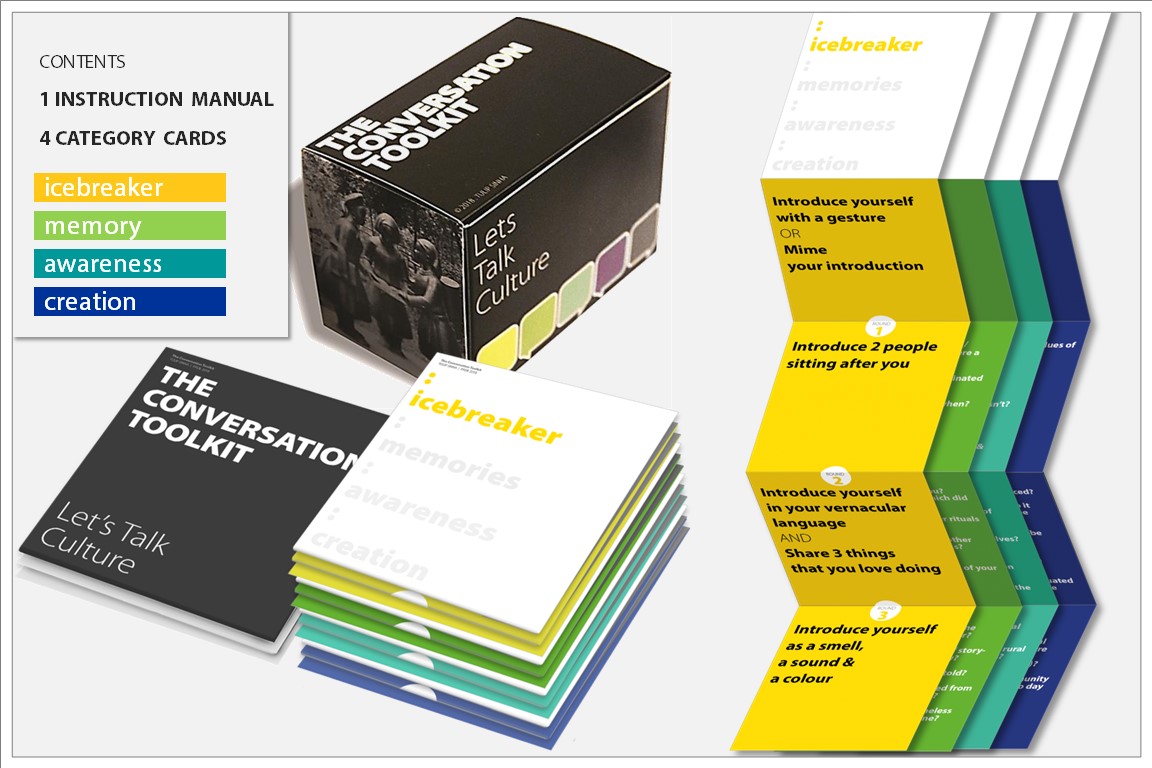

The practice of meaningful communication is a necessary way to build an ethos of investigation, knowledge creation and sharing.

This is the belief of Tulip Sinha, a faculty member at the Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design & Technology in India.

In fact, her home country has a wealth of alithic knowledge systems, which heavily rely on oral transmission (known as “shruti” in Sanskrit).

Therefore, when she started to notice that the art of making conversations was fast becoming an uncomfortable affair among her first-year Industrial Art & Design Practices students, even risking disappearance, she knew she had to do something about it.

“The art of listening and engaging attentively was dying too,” she points out.

“The loss of this most natural mode of communication disengaged students from their immediate environment, affecting their practice as young designers.”

In response, she decided to develop the Conversation Toolkit in 2018, to “foster active communication, socio-cultural connections and mine the knowledge born out of social interactions”.

The Conversation

Toolkit and its contents

The Conversation

Toolkit and its contents

Built around the notion of culture, the toolkit consists of an instruction manual and four colour-coded decks of cards, split into the conversation categories of Icebreaker, Memory, Awareness and Creation.

Best played in groups of four or five for a class of up to 30 students, it follows a pre-set sequence where each player responds to a set of questions within the conversation category.

These are meant to operate as scaffolds for the conversations that transpire.

The toolkit encourages discussions that decode the complexities of culture, while also creating a new hypothetical culture by the end of the game.

At the same time, the students are creating a culture of conversation within the classroom as well, making it a reflexive practice.

More broadly, she created the toolkit on the understanding that designers are change-makers who need to insert their products or services within socio-cultural realities with sensitivity.

“The Conversation Toolkit works on the premise that conversations are a form of ‘intellectual capital’ that can be used as a simple tool of investigation for the practice of design and life,” says Sinha.

“It also assumes that critical questions can emerge from meaningful conversations because learning may not always take place from exchanging or eliciting right answers alone.”

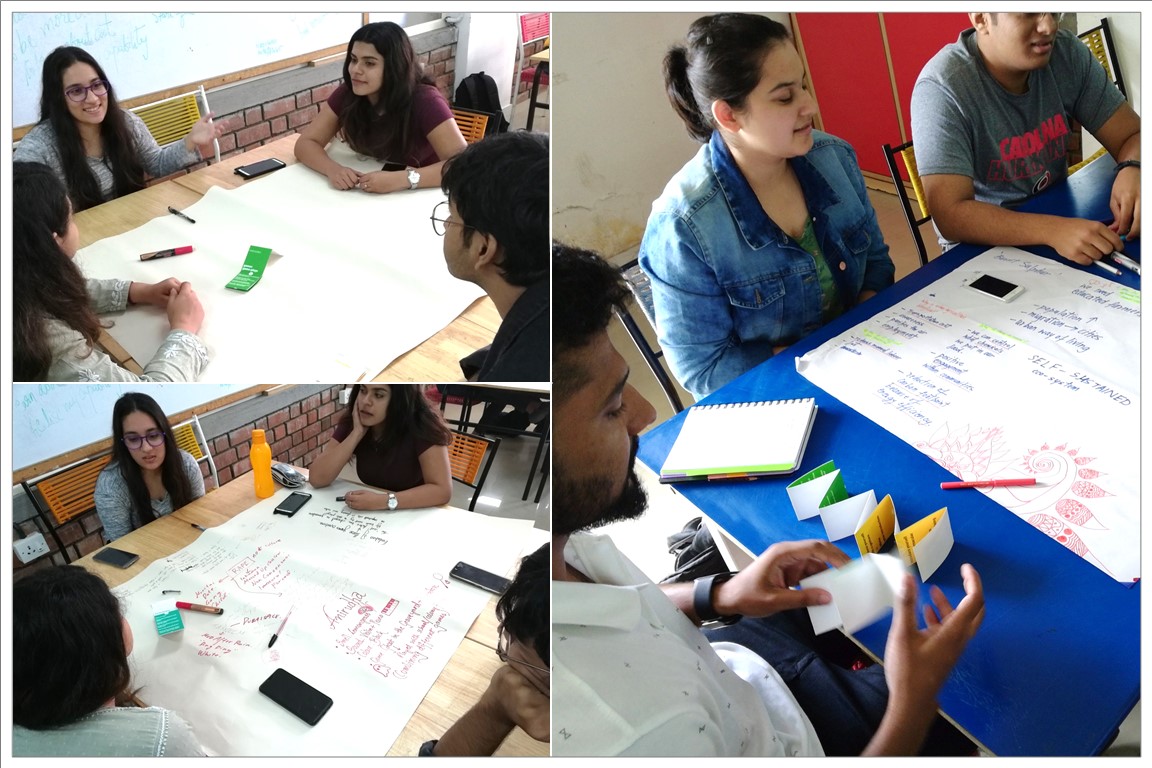

To test its efficacy, she used it prior to a field trip to the rural area of Bhuj, in the Kutch region of Gujarat, with her students.

Students engaging

in conversation with each other.

Students engaging

in conversation with each other.

The intention was to expose them to the socio-cultural-political realities of rural India, while gaining fresh perspectives on the art of archiving memories and adopting and adapting tools of research to engage with the local tribal communities living there.

Her observations were encouraging:

- My role as a facilitator stopped at initiating the game. Thereafter, it was co-managed, so I was able to listen more and also participate. We had finally created a non-hierarchical, unthreatening space for communication.

- Mobile phones were not in use for two long hours. The students enjoyed listening to each other and wanted to finish the game. This allowed for the learning process to be more immersive and deliberative.

- The conversations moved from familiar-subjective topics to more unfamiliar-distant topics, requiring more deliberation.

- The conversations often steered away to very interesting directions that had not been anticipated. For instance, questions were asked around whether the notion of home is cultural. Another was if there were any rape-free cultures in the present day and what could be learnt from them.

- The newly designed cultures were very well structured with solid reasons for their existence.

Students using the

Conversation Toolkit to have a discussion.

Students using the

Conversation Toolkit to have a discussion.

“Creating, sharing and seeing the toolkit in use reassured me of the value of conversations,” reflects Sinha.

“It made me wonder why it has not been considered and employed as a fundamental building block in all learning environments.”

Click here to read more about the other stories