St. Joseph’s Institution (SJI) could easily be mistaken as more than just a school.

Stroll along its corridors and it is hard to miss the myriad of artworks by SJI’s students both past and present that hang on the whitewashed walls, evoking the effect of a gallery.

Beyond their two-dimensional presentation, art teacher Ms Jessica Cheng wondered if it was possible to do more with them.

“How can we honour these artworks? How can the school transform into a living museum to share the everyday narratives of students who walk these corridors?” she thought.

Working from January to March this year, her students and her launched an art trail on a smartphone application, which uses augmented reality (AR) to tell the stories behind the artworks.

In doing so, it allows participants to learn more about the pieces by the student artists, such as the thought process behind their composition, and tells the story of the school.

Students

testing each other’s AR design by scanning the artworks along the

school’s corridors.

“The idea of using AR emerged unsurprisingly from their rich experiences with new age digital games,” says Ms Cheng, when she mooted the question of how to transform the school’s corridors to eight of her students.

While the concept was exciting, she admits to have felt intimidated at the start.

On one hand, there were some local museums like the National Gallery Singapore that had integrated AR into their exhibitions, but they did not have their own proprietary platforms.

On the other hand, AR technology was complex and mainly for professional or commercial use.

“We quickly realised that we had to seek an alternative approach and learn from scratch,” she adds.

They started by reaching out to at least four different companies specialising in AR to obtain their inputs on how to execute their idea.

After evaluating their options, they decided to use the Austrian-based AR application, Artivive.

Not only did it have a free platform, but there was no need to have extensive prior knowledge on coding, which was then an important skill to have in mastering AR.

Her students dove straight in, self-learning via the tutorials on Artivive’s site to ensure the images and videos in the app appeared smoothly when the smartphone was pointed at the artwork.

"As first-time coders, there were many failed attempts when the AR effects could not align or animate.”

"However, they remained resilient and resolved the glitches independently through trial and error and learning from online forums.”

A

student learning to apply AR effects onto an image.

Once they had overcome the challenges, Ms Cheng’s students took the project a step further and transformed it into a treasure hunt.

A route through the campus was decided on and through a narrative conveyed at each stop, the pieces came to life.

For example, along the corridor of the Year 1 classroom block is the painting of St John Baptiste de La Salle, illustrated by Mr Reuben Pang (from the Class of 2006) in hues of blue and green, showing de La Salle's rough sea journey.

He was a French priest who founded the Brothers of the Christian Schools that established SJI.

The artwork “talks” about the Frenchman’s faith in children and young students, before giving hints to the next “treasure” along the hunt that embodies the spirit of teachers dedicating their time to help students learn.

The painting of St

John Baptiste de La Salle along the art trail.

The painting of St

John Baptiste de La Salle along the art trail.

While the learning curve was very steep and the COVID-19 pandemic forced them to hit pause on the project, Ms Cheng says the experience has nonetheless been a novel one that other schools could consider.

“We hope that our initiative can empower others to reshape their experiences along their school corridors and employ the use of technology to tell stories and cultivate new ways of seeing and learning,” she shares.

Is Design Thinking really useful?

That was the question that arose in Mr Joos Van Cauwenberghe’s mind, after he noticed there was no significant difference in the quality and depth of the projects between his seventh and 12th graders when they applied its theories.

“It suggests that during five consecutive years of practice, Design Thinking feels good to use, but fails to produce the shifts in individual core design skills and mindsets,” says the innovation coordinator at RHIZO, a school community in Kortrijk, Belgium.

Certain that this could be remedied, Mr Van Cauwenberghe went on a quest to find out why this happens and how to mitigate it.

The Reason: One of the problems is that the current Design Thinking resources are often presented as a one-size-fits-all solution. They describe the design process and mindsets in general, and provide one step-by-step instruction on how to implement a particular design method. There is a lack of curriculum solutions that can scaffold the students’ design abilities from novice to intermediate or expert status. As a consequence, when students execute design tasks, teachers offer the same level of knowledge and coaching over and over again and expect different results.

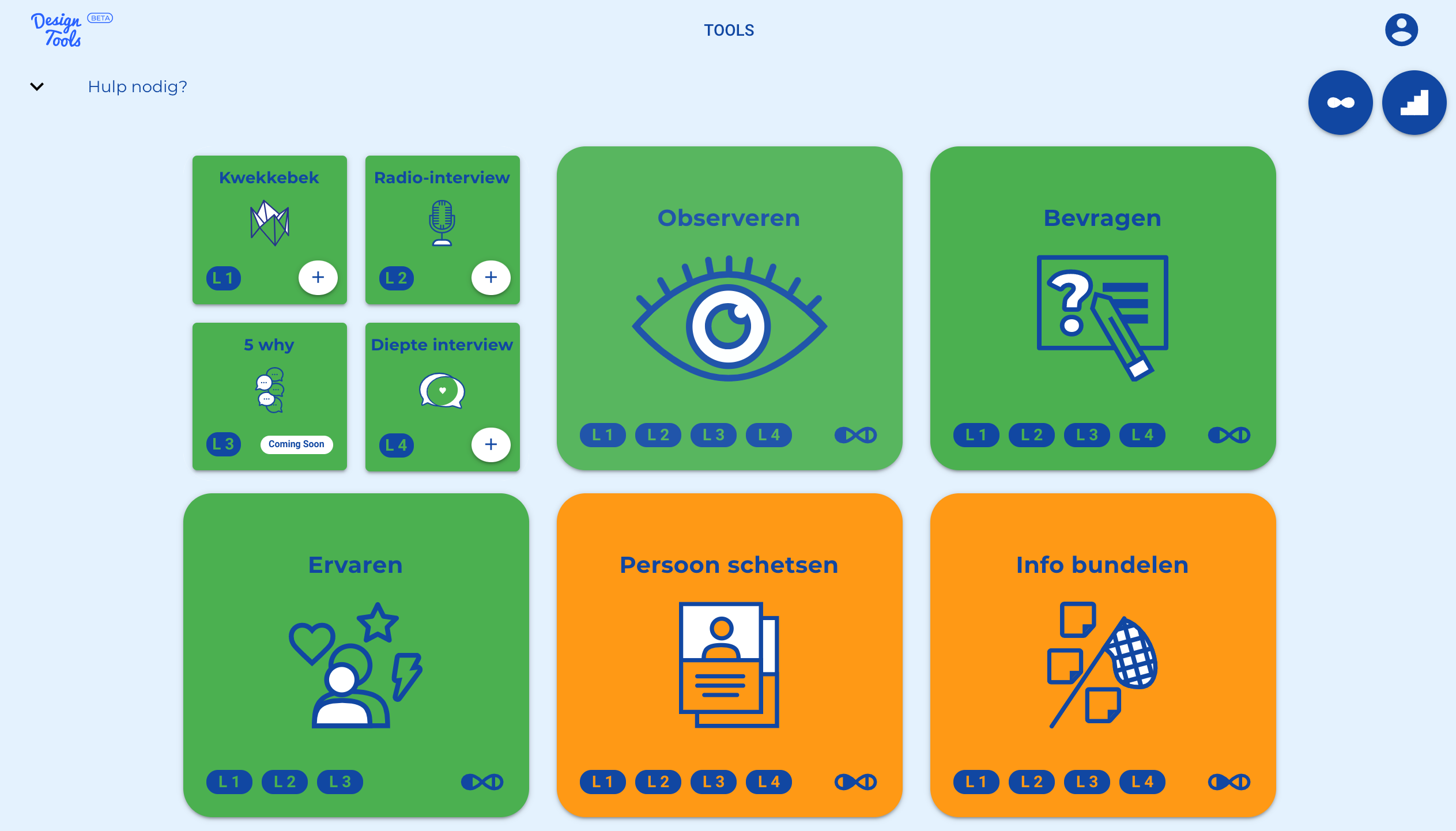

The Solution: Inspired by the work of expert practitioners like J. Schell and E. Korsunskiy, we started prototyping Designtools in 2019. In essence, it is a learning pathway for human-centred design in K-12 education. To help scaffold learning, we used a backward design model and asked ourselves a series of questions:

Learners and

facilitators can select and coach each design activity in up to four

levels of complexity.

Learners and

facilitators can select and coach each design activity in up to four

levels of complexity.

In this way, we deconstruct well-researched design methods into their underlying knowledge, skill and attitude components. In co-creation with teachers and students, we identified 20 actions learners recognise and frequently have to demonstrate while practising Design Thinking: observe, define insight, pitch, etc.

For each of these actions or “verbs”, we developed lessons, with up to four levels of complexity, thereby providing a scaffolded path towards mastery. In each lesson, we include elements of game design at the lower skill levels and strategically promote self-efficacy (mastery examples, effort-specific feedback, etc.) in Design Thinking, that leads up to them regulating their learning.

The

Designtools interface where users can construct and adapt their

design journey in a few clicks.

The

Designtools interface where users can construct and adapt their

design journey in a few clicks.

Next Steps: Designtools is a peer-generated and open-source resource for teaching Design Thinking in K-12. Through the web-app, both teachers and students can structure project-based courses or capstone projects in a few clicks, and gradually increase their confidence in their ability to think and act creatively. We hope to initiate further research on how to teach Design Thinking effectively in K-12 education. We will also continue prototyping Designtools so it supports professionalising the field of K-12 design education in Belgium and abroad.

Designtools offer users open-source lesson

slides, example worksheets, rubrics, instruction videos and expert

facilitation tips.

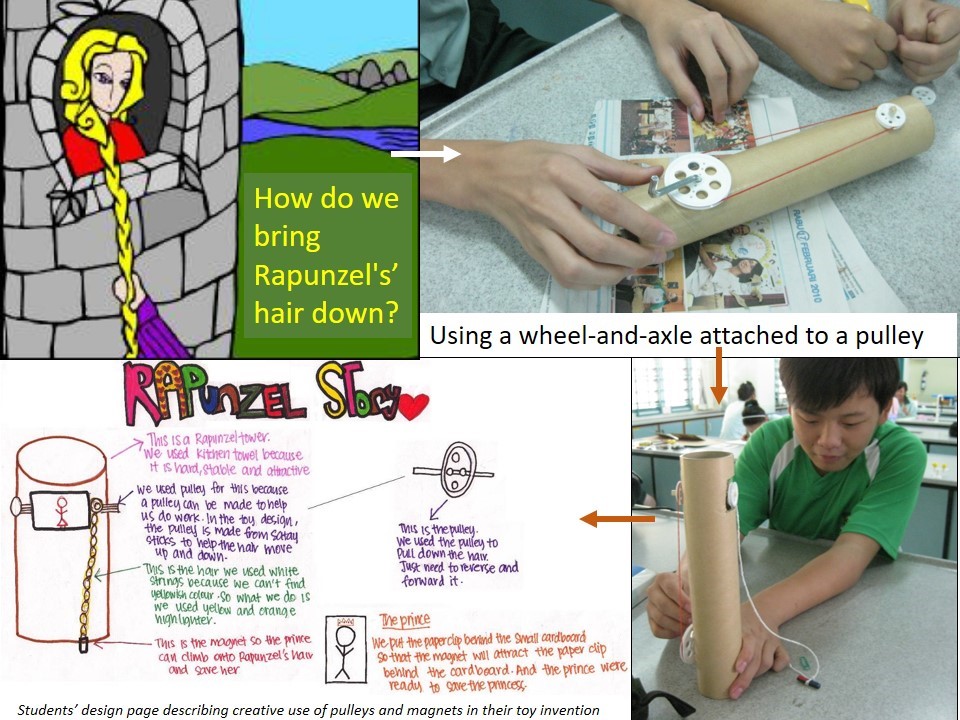

Rapunzel is a fairy tale of a beautiful girl who was trapped in a tower by an evil sorceress.

She grew out her hair, which allowed a prince to climb up it, meet her and they fell in love.

In the hands of Dr Nazir Amir and his class of Secondary Two Normal Technical (NT) students at the former Greenview Secondary School though, this story became an unexpected opportunity to learn Science, Art, English and even Computer Application.

It all started when they were volunteering at MINDS (Movement for the Intellectually Disabled of Singapore) and noticed how several intellectually disabled pre-school children were easily distracted during story-telling time.

This, despite teachers using picture cards, media-clips and puppets as teaching aids.

Together, he and his students came up with the idea of designing and crafting toys during their Science lessons to tell fairy tales and nursery rhymes to the children.

“This approach motivated my students to be immersed in a problem-solving activity that led them to brainstorm ideas the through creative use of scientific principles,” says Dr Nazir, who is now a Master Teacher at the Academy of Singapore Teachers, specialising in Educational Support.

For instance, the scene of the prince climbing the tower in Rapunzel was made from a kitchen towel roll integrated with a wheel-and-axle attached to a pulley.

White thread coloured with highlighters to make it blonde was wound around it and a magnet was concealed at one end.

The cut-out of the prince had a paperclip glued to its back, so that it would be attracted to the magnet and as the thread was pulled up, it appeared as if he was ascending the tower.

The students

illustrating how they came up with the toys for Rapunzel.

The students

illustrating how they came up with the toys for Rapunzel.

Apart from teaching them Science, he collaborated with other teachers to allow the students to learn respective knowledge and skills across different subjects.

They honed skills in narration, dramatisation and public speaking during English lessons, as well as graphic and animation skills in PowerPoint during Computer Applications lessons, enhancing the presentation of their stories.

But Dr Nazir did not stop there – he also saw to it that school values were consciously reinforced.

“Students learnt to respect themselves and others; they were trained to be resourceful by making use of recycled materials to fabricate their toys; they were taught to be responsible for the care of their own design portfolios and toys; and they learnt important lessons about resilience.”

Knowledge

and skills from different subjects including Science, English and

Computer Applications were also learnt and integrated in the project

by the students.

Knowledge

and skills from different subjects including Science, English and

Computer Applications were also learnt and integrated in the project

by the students.

While there were many moments when their prototypes failed in the initial stages, they were encouraged to try again and not give up so easily.

He reveals that the pre-school children at MINDS were very receptive to the story-telling experience delivered by his students, and grateful to them for making learning joyful.

This project eventually spanned over 10 years, and in doing so, reached out to many more children in pre-schools and orphanages.

As a result, Dr Nazir and his students were invited to collaborate with the Early Childhood Development Agency on a number of initiatives.

They have conducted professional development workshops for pre-school teachers, guiding them to make similar Science-based toys for children in their own schools, as well as STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts & Mathematics) workshops for parents of pre-school children.

“The project has led to pre-school children, their teachers and parents feeling happy and contributed to increasing the self-worth of my students,” Dr Nazir remarks.

The project has contributed to the self-worth of

the Dr Nazir’s students and well-received by pre-school children,

their teachers and parents.

The project has contributed to the self-worth of

the Dr Nazir’s students and well-received by pre-school children,

their teachers and parents.

How many of us can actually say that as students, we showed our appreciation to and bonded with the non-teaching staff in our schools?

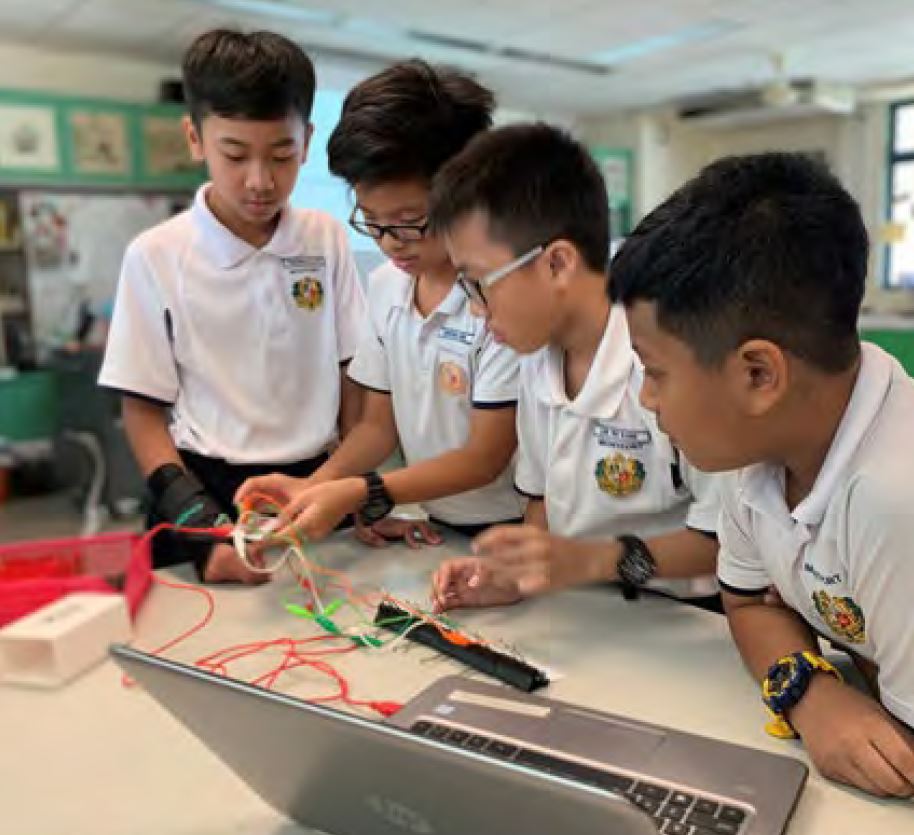

Identifying this as a great learning opportunity, Mr Zhane Tang and Mrs Amy Khoo of Montfort Junior School guided their Primary 5 students in 2020 to use design thinking to address it.

In doing so, it also aligns with the school’s belief in offering a future-centric education.

Mr Tang shares that the Art and Music departments decided to collaborate and use Makey Makey to help the students build their own digital instruments.

Makey Makey is an invention kit that turns everyday objects into computer keys. These can then be programmed to become musical notes.

The next step: getting the pupils to identify a non-teaching staff they would like to get acquainted with.

“Empathy plays a big part in the design thinking process,” says Mrs Khoo.

“We had the students approach and conduct an interview with their non-teaching staff of choice to get to know them better.

“Pupils gathered information like the staff’s favourite song, colour, hobbies and instrument and found out more about their childhood.”

All these were taken into consideration as they made the “digital musical instrument”.

The students learnt the songs the non-teaching staff liked by using the Orff Approach, which is a method that uses singing, dancing, acting and the use of percussion instruments.

In this project, the xylophone was the preferred option.

“They figured out the music scale and notes required to perform their songs.

“They then proceeded to do coding using Scratch, which was a required aspect to incorporate into the Makey Makey kit,” explains Mr Tang.

The design of the prototype came next, crafted based on the non-teaching staff’s preferences as conveyed during the interview.

Students

experimenting with the Makey Makey kit.

Students

experimenting with the Makey Makey kit.

The students then presented the “digital musical instrument” and performed for The students then presented the “digital musical instrument” and performed for them.

One group interviewed the school’s principal, Mr Wilbur Wong, who told the boys about his passion for rugby and cycling.

They went on to create a mock-up of a rugby field with a cycling track around it and programmed rugby balls with musical notes to perform a song.

While obstacles were encountered, such as how to ensure their instruments produced the right sound, both teachers were happy that no one gave up.

An end product by

one of the students.

An end product by

one of the students.

Instead, the students learnt how to adapt quickly and remained engaged throughout the project by asking questions, seeking clarifications and putting themselves in the shoes of their “clients”.

Mrs Khoo admits that the learning curve was steep for everyone, including the teachers.

But while the end products of this project were not perfect, Mrs Khoo and Mr Tang were very encouraged by the high engagement of the students and support from their colleagues.

“It’s not every day that the students get to use the skills they have learnt to solve authentic problems,” she says.

Adds Mr Tang, “We could see the spark in their eyes when they presented their project to the non-teaching staff.

The school

bookshop owner playing with the outcome of the students’

project.

“We believe that the skills they learnt in this project will definitely be an asset to their future.”

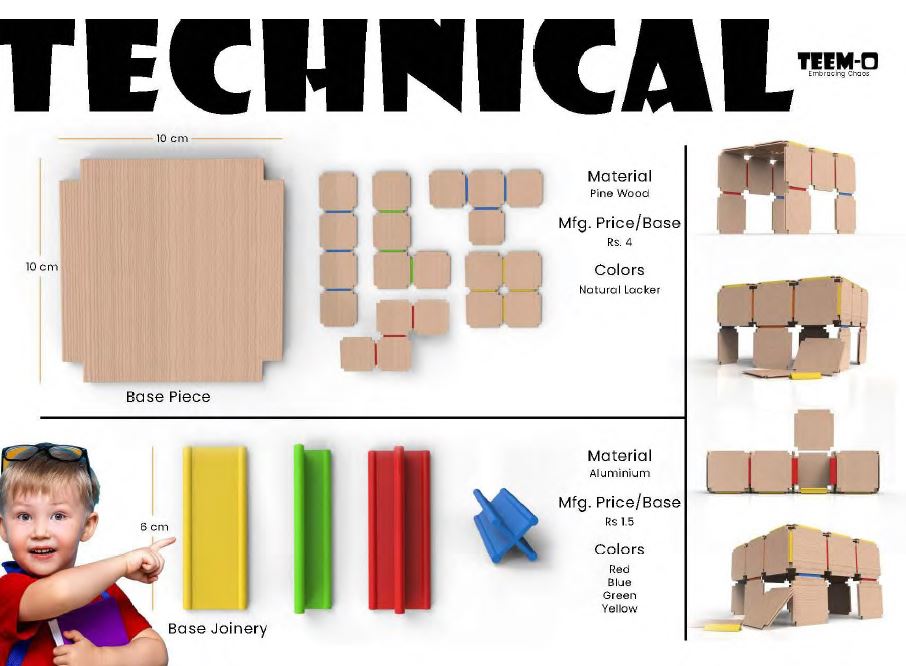

What skills should we teach young children today to prepare them to enter the workforce in 15 to 20 years?

This was the question Mr Harshit Thareja posed to himself, as he considered the topic for his graduation project in 2019 at Pearl Academy in New Delhi, India.

Eight months and much research later, he concluded that soft and life skills were the answer.

Understanding a child’s behaviour was part

of the research Mr Thareja did.

“I realised there is no tangible skill which will definitely be used in the future, although digital, social and emotional skills will increase in importance by 2030,” he explains.

“I decided to reverse engineer the skills I have and believe will remain with me for the years to come, and found them to be communication, presentation and empathy, just to name a few.”

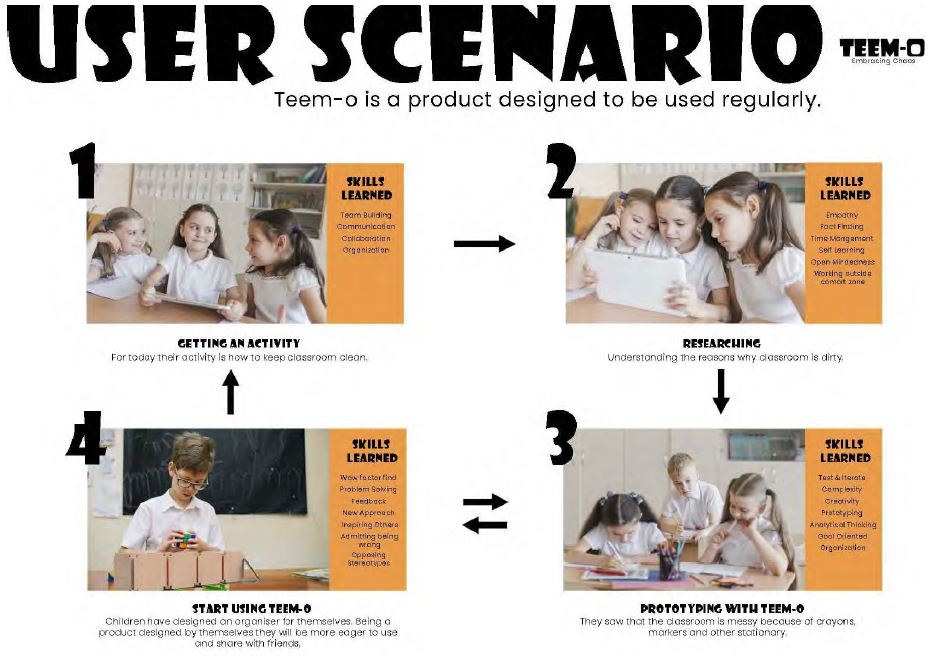

The result was TeEMo, a plug-and-play, energy-based prototyping kit that teaches problem-solving through design thinking and experiential learning.

The modular system is made up of squares of pine wood in various sizes that are connected by aluminium joinery to create different types of structures.

It is coupled with a teaching guide on how to impart life skills on children aged four to eight.

TeEMo is

made up of squares of pine wood connected by aluminium joinery.

For example, during “Green” week, where they are taught how to keep their surroundings clean, the children can use TeEMo to make products such as dustbins, which can even be used in their classrooms.

“While doing so, they subconsciously are learning how to research, ideate, prototype and test, which are processes of design thinking.

“The kit amplifies learning and channels chaos into productivity, without compromising the fun of building blocks.”

Mr Thareja shares that TeEMo was also conceptualised on the back of what he learnt during design classes at Pearl Academy, including 26 different types of life skills that have since been ingrained in his memory.

Children

subconsciously learning how to research, ideate, prototype and test

using TeEMo.

Funnily enough, he also noticed that there is an important similarity between designers and children in that they both have “chaotic minds”.

“Designers know how to embrace chaos and turn it into meaning for people, while children use chaos to explore their creativity,” he says.

A product like TeEMo will hopefully guide the latter group to crystallise their innovative mindsets into something useful for society.

Next up for Mr Thareja, prototyping TeEMO at Design Process, the studio he has just set up.

He intends to test it with various schools and hopes to turn it into a commercial product that in due course, will help generations of young children be future-ready.

How can young people become successful after a failing school trajectory? This is what a team of Belgian educators and researchers, led by Mr Roel De Rijck and Mr Joos Van Cauwenberghe, asked themselves. Their solution is JUMPlab, a personal development programme launched in 2019 that uses the power of design to transform how young people aged between 16 and 22 years old can search for opportunities, which they otherwise would never have dreamt to do.

Understanding the challenge: Some 30 percent of Belgian youths find themselves lost in their current course of study. It is precisely this group of “misfits” that JUMPlab is targeting. From their perspective, the school system has failed them. This is why they become withdrawn, avoiding all activities that they perceive as potentially unpleasant and losing any willingness to take risks and explore.

Researching the solution: The programme started with design-driven research for one year, investigating the levers to pivot a negative school experience into a successful career. Upon discovering a formula, we now call these individuals “jumpers”, as they are able to make an unexpected career “jump” and find fulfilment in life. JUMPlab was therefore built on three core levers all jumpers use to make the leap:

1. Jumpers never jump alone – There is always a crucial third party

pushing the jumper to explore new professional opportunities.

2.

Jumpers build and leverage networks – While exploring, jumpers develop

and leverage a personal support network.

3. Jumpers design their

own life – Jumpers operate as designers of their own life, without even

knowing it.

The typical size

of a JUMPlab team has eight JUMPers with two coaches.

The typical size

of a JUMPlab team has eight JUMPers with two coaches.

The JUMPlab programme:

Step 1. Experience a first JUMPlab

First, we build

creative confidence by letting them participate in several Design

Sprints. These Design Sprints are such an unexpected, inspiring

experience it enables us to become the personal mentors to help them

jump.

Step 2. JUMPlab XL, pushing the boundaries

We help

JUMPlab teams participate in competitive hackathons to build their

design skills further, discover new networks and get inspired by the

invited speakers. As a result, the youths get rid of their

head-in-the-sand mentality and see new opportunities for their future.

The youths

pitching their insights and solutions to KV Kortrijk, a soccer club

from Belgium.

The youths

pitching their insights and solutions to KV Kortrijk, a soccer club

from Belgium.

Step 3. Rebuild your life in a LIFElab

We persuade

the youths to use their design skills for the good of their own life and

design a new future. By doing so, we stimulate them to discover and grow

on a personal level. Questions such as “what do I want to become?” shift

to “what do I want to grow into next?”. This helps them turn a

stagnating life into an action-oriented one full of possibilities.

Prototyping solutions

in a JUMPlab programme to make a soccer club more attractive to a

broader range of young people.

Prototyping solutions

in a JUMPlab programme to make a soccer club more attractive to a

broader range of young people.

Outcome: JUMPlab has quickly become loved by a community of misfits who are willing to shift their mindset and push boundaries to take life into their own hands, building self-awareness on the way. To them, JUMPlab is just the beginning, and they are ready to inspire others whenever possible.

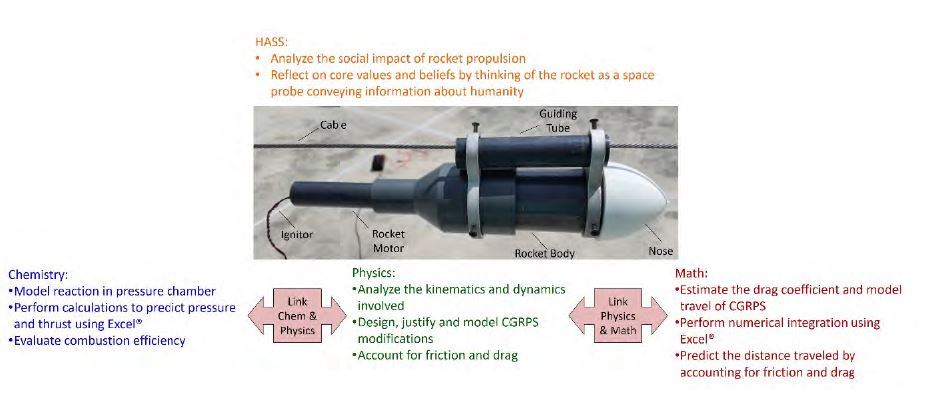

When the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) assembled a time capsule to mark its 10th anniversary in 2019, one of the items it included was the prototype of a cable-guided, sugar propulsion rocket.

Conceptualised by a group of senior students in 2015, it forms the basis of a compulsory week-long design project, named 2D, done by all freshmen of SUTD.

The first-year students are expected to modify the rocket to ensure it hits the target distance of between 17m and 18m.

In the process, they are expected to apply knowledge learnt from Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics and Humanities, Arts and Social sciences, which are subjects they are concurrently taking.

Final design of

the cable-guided, sugar propulsion rocket and the link between the

four subjects.

Final design of

the cable-guided, sugar propulsion rocket and the link between the

four subjects.

“The intention behind 2D is to demonstrate to our students that projects in the real world are multi-disciplinary in nature,” says Dr Apple Koh, who is in charge of the design project.

“After they completed it, they must also be able to convey their ideas around it, either through a report or presentation, which makes the students realise they need to learn to communicate well.”

2D, however, was not always about modifying a cable-guided, sugar propulsion rocket. In 2014, it was about designing a race strategy to achieve the shortest lap time with minimal fuel consumption with a hydrogen fuel cell toy car.

“The implementation was challenging, with comments that the toy car was too slow, not exciting enough and the link between all the subjects was weak and contrived,” explains Dr Koh.

“The students felt they had to do it because it was a compulsory assignment, but they did not think they benefitted from it.”

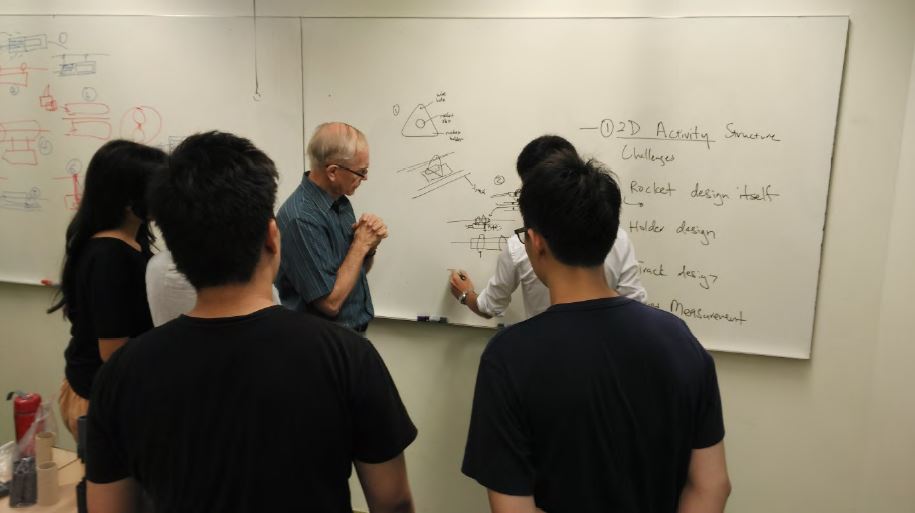

Determined to mitigate this, a group got together and volunteered their free time to come up with a brand new 2D design project idea.

The senior

students, SUTD instructors and MIT Prof Kim Vandiver who worked on

the cable-guided, sugar propulsion rocket.

While this was typically the domain of the university’s lecturers, Dr Koh was happy to let the students have a go at it.

To prepare for this, students attended a series of workshops on the design and implementation of past 2D activities, before deciding they would design a sugar propulsion rocket.

A literature search was done to better understand the Chemistry and Physics of sugar propulsion rockets, together with brainstorming with faculty members from SUTD and the MIT-SUTD Collaboration Office on how to design its motor, body and guiding system.

The senior

students discussing their designs with MIT Prof Kim Vandiver.

The rocket was then prototyped and built, before being launched in 2016 for SUTD’s freshmen to work on for their 2D design project.

Dr Koh notes that it was rewarding to see the students contributing to SUTD’s curriculum, developing it with minimal advice from the faculty.

Not only did they understand and address any concerns, but they were also able to evenly incorporate knowledge from the four subjects into this edition of 2D.

For instance, they acknowledged that the fuel mixture of sugar and potassium nitrate was dangerous and proposed to have it mixed by hand instead of using a machine.

Trial of an

early iteration of the cable-guided rocket body design.

But the biggest reward was probably seeing how much the Year 1 students enjoyed working on 2D.

“Despite the amount of work, they found it exciting, especially when the rocket took off with a loud boom,” points out Dr Koh.

“We were also very happy that the senior students worked so hard to improve the design project to help their juniors.”

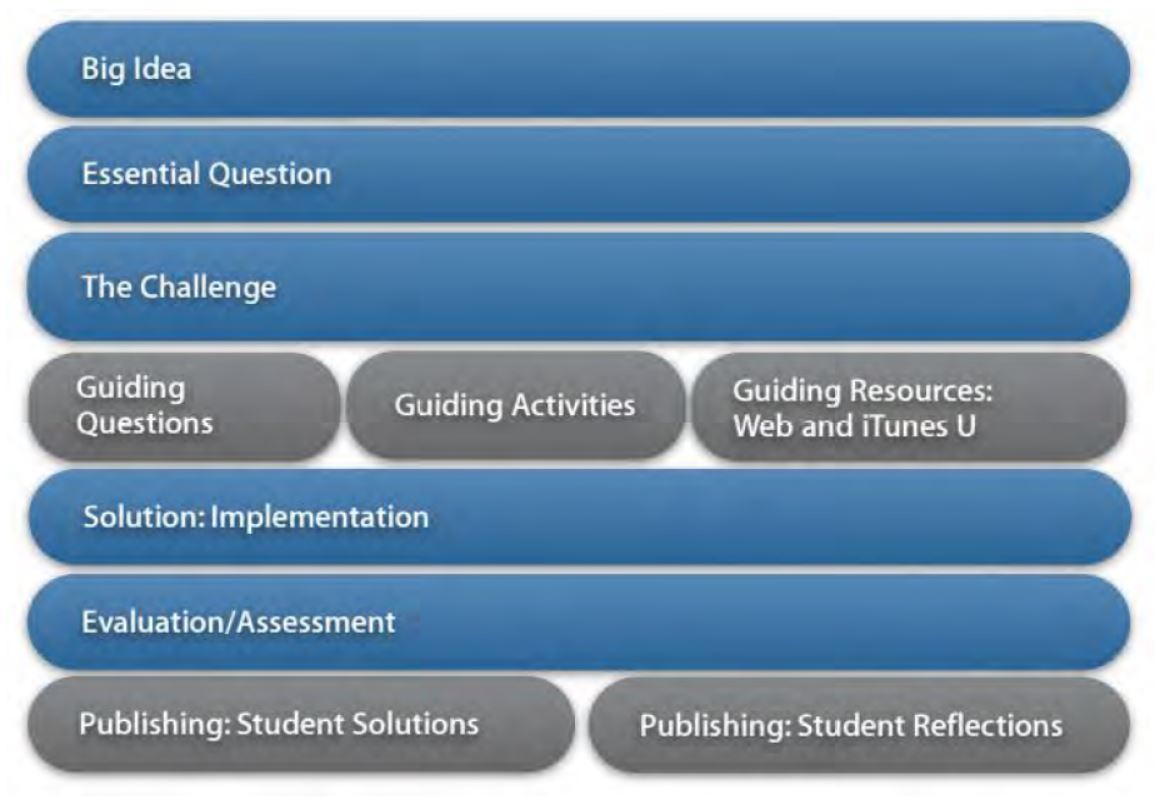

The design thinking framework is a familiar one to many educators.

In the hands of the School of Science and Technology, Singapore (SST), it has been developed to make it even more relevant for its students aged 13 to 16.

While initially only elements of design thinking were leveraged as part of the curriculum by the Art, Design, Media and Technology (ADMT) department, the school gradually introduced it to other departments.

Mohamed Irfan Bin Darian, Head of the ADMT department, breaks down the three phases of its development and demonstrates how it evolved in the past decade.

2010-2012 | The Initial Years: From Challenge Based Learning To Design

Thinking

How do you unite 200 students coming from over 150 primary schools? This

was the

earliest challenge faced by the ADMT department. In response, it came up

with a

theme that was relatable to everyone: Saving the Environment. The

students were

tasked with coming up with projects relating to it, created by applying

the Challenge

Based Learning (CBL) framework, favoured for its strong focus on problem

solving.

The Challenge

Based Learning framework

The Challenge

Based Learning framework

By the second semester, another theme was added, this time inspired by the Singapore government’s ministerial white paper on the issues faced by the silver generation. The Elderly Challenge involved the students understanding what seniors faced, as well as nudged them out of their “teenhood social bubble”. This was done through interviews and interactions with the elders in their households, and/or their interactions during their service learning experiences where the students interacted with them to comprehend their needs.

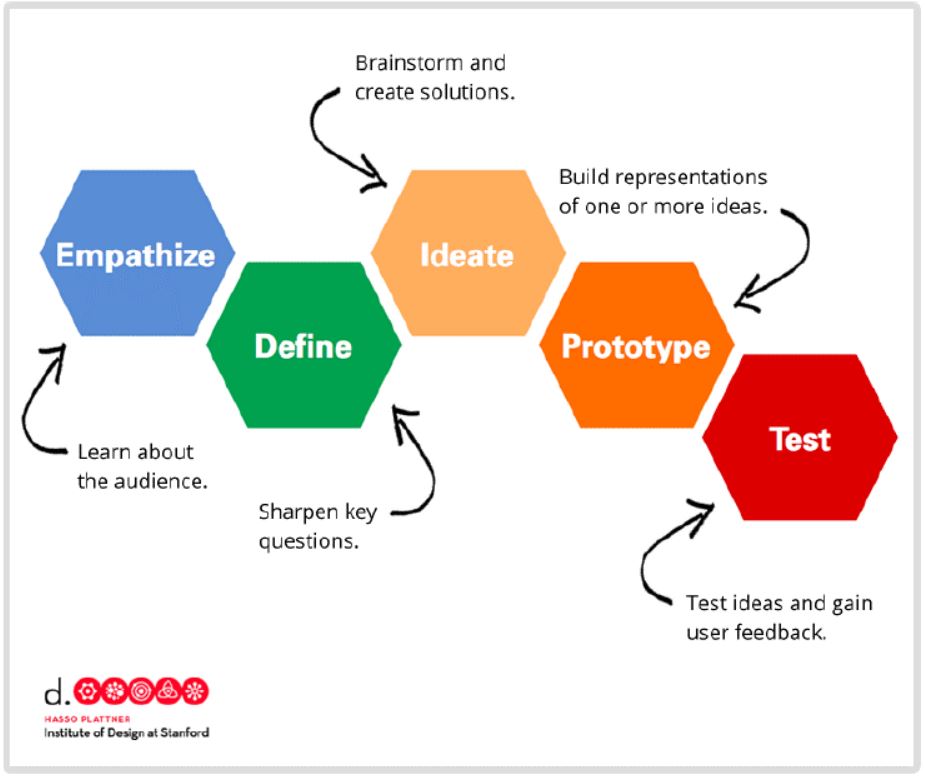

As the department continued to evolve the offerings of the curriculum , the team decided to map out the various stages of the CBL framework to that of design thinking. For example, instead of starting out on the initial stages of Engage and Understanding the Big Idea in CBL, they felt that more could be done to get students to understand better their target audience by mapping and refining this stage to the Empathy stage in design thinking. This transposition also helped them ensure that students are not missing out or confused about the important stages when a transition was made from CBL to design thinking.

2013-2016 | The Developing Years: Strengthening Our Design Thinking

Practices

Our focus turned to expanding and increasing the depth of the students’

understanding of design thinking, as well as ensured it was correctly

applied to their

projects.

The Design

Thinking framework

In 2015, the ADMT department embarked on a collaboration with 3M Singapore to craft a unique STEAM-centric learning experience for Secondary 1 students, in line with the innovation 3M is known for. It soon evolved into the SST-3M Innovation Challenge, which was later renamed to SST-3M InnoScience Challenge in 2017. Solutions for real-world problems were sought and one project was selected to win the Challenge each year.

Secondary 2 students taking the Architecture Design module also became privy to the design thinking framework and process. In one project, the World Expo 2016 was used as a starting point for students to apply it to understand the “essence of the country” they had selected for deeper research. They worked on understanding the symbolisms in the country of their choice to represent them better in the pavilions they designed.

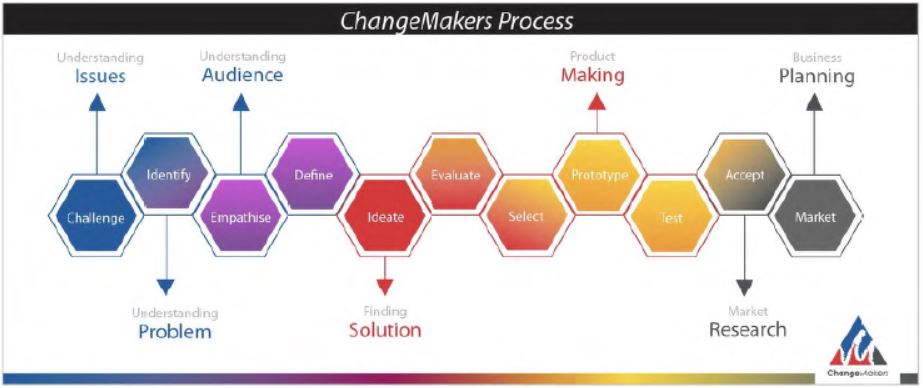

2017-Present | The Expanding Years: Rethinking Design Thinking

This period saw the integration of design thinking with other parts of

the school. The

ChangeMaker (CM) Programme was born, unifying the curriculum of the

ADMT,

Information and Communication Technology and Innovation &

Entrepreneurship

departments. This was done with a strategic intent of acknowledging that

each child

is different in terms of their abilities and preferences.

The

ChangeMaker Process

The students then had to identify the roles that best fit them, and underwent specific training in that particular subject matter during their lessons. Concurrently, they were reminded that their diverse expertise would converge and culminate towards a final makeathon-type event challenge. Organised over a period of three days and one night at the end of Term 4, the event aimed to provide the students with a valuable and significant learning experience to see the application of these content areas into a highly compressed, signature event.

Within the teaching staff, they updated the CM Programme, bearing in mind that it must adhere to or have a familiarity with the current model, for ease of continuity. A redesigned framework was drawn up to take into account the offerings of the various content areas, as well as to enhance the students’ learning experiences, especially after the testing and evaluation stages in the original design thinking framework.

Heavier emphasis was placed on getting students to understand the issues at hand and their audiences. Beyond the testing stage, an addition was included to ensure that the students realised their ideas had to be accepted and marketable in the real world.

Click here to read more about the other stories